“Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.”

In his seminal work, “Thinking Fast and Slow”, Daniel Kahneman poses the following question: is Steve more likely to be a librarian or a farmer?

Have a think about it for one second. If you’re anything like the majority of other people, your immediate response is likely to classify Steve as a ‘librarian’.

But, why exactly is this? The answer lies in your ‘associative memory’ and your tendency to think ‘fast’1. Each and every time you observe a description like this, your associative memory almost instantaneously connects Steve’s personality traits with a stereotypical librarian.

Most importantly, though, this is a flawed thinking pattern based on lazy assumptions and stereotypes. Did you know that there are five times as many farmers as librarians in the United States? What if I told you that, in addition to this, the ratio of male farmers to male librarians is even higher?

Suddenly, the question of Steve’s identity becomes much harder to answer.

The flawed mind of human beings

Why the preamble on Steve?

Because - presuming you are a human being - this flawed thinking style affects you too. In particular, it affects how you select your password. Yes, that important piece of data which secures your connection to various applications across the web.

And you’re definitely not the type of person who sets ‘one’ password for every service now.. are you?

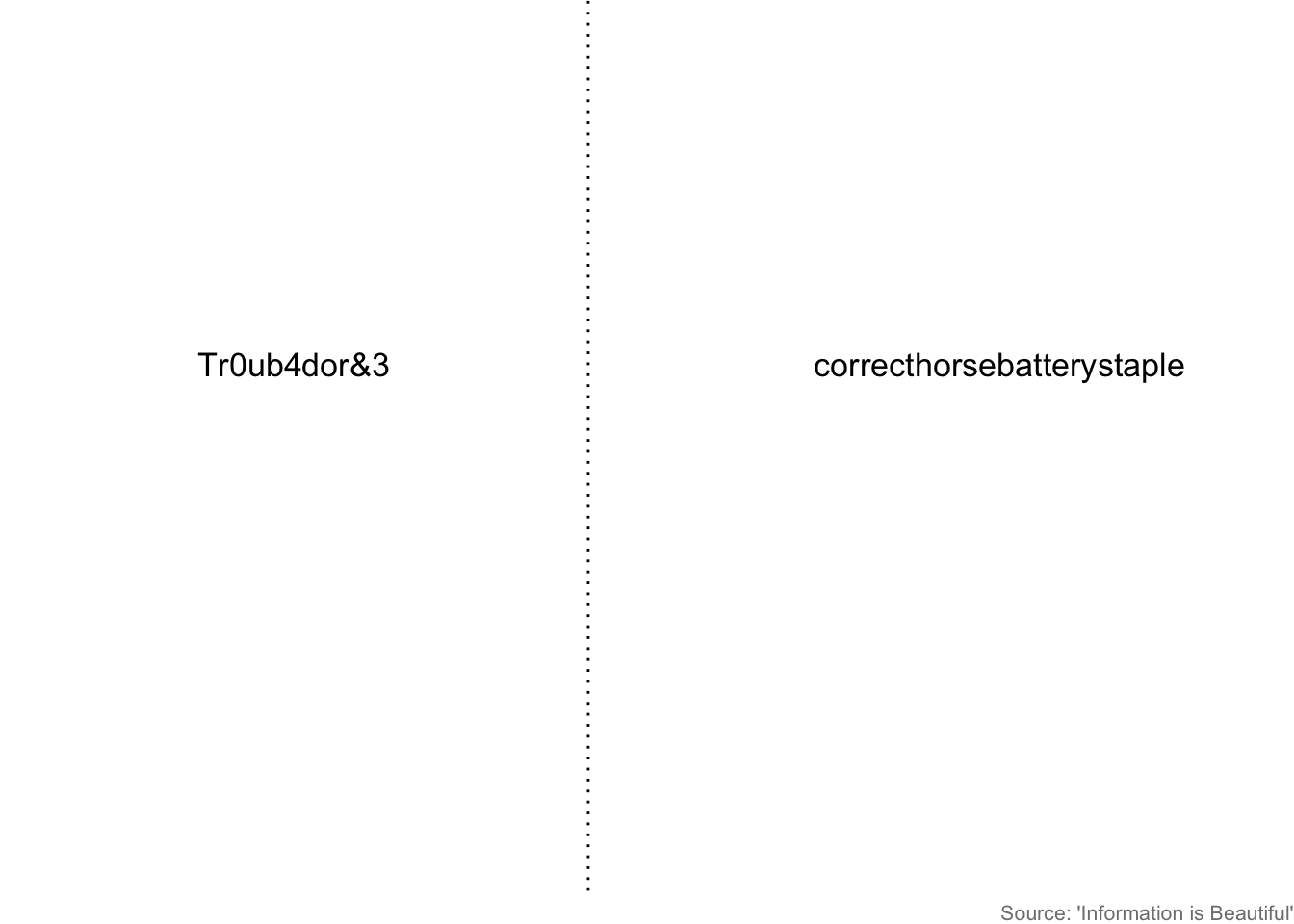

Take for example the following password choices, superbly analysed by ‘xkcd’:

Most people, if forced into a choice, would opt for the password presented on the left-hand side, due to its perceived complexity. If you’re one of these people, then unfortunately you’d be taking a relatively high risk.

You might be wondering how the alternative choice, with no special characters or numbers at all, is ‘stronger’. It’s to do with something called ‘entropy’.

Think of entropy as ‘information’. Every password encodes a certain level of information - the higher this level is, the stronger your password is. Generally speaking, the longer your password is the more entropy or information it has. That’s why option 2 is better: it’s longer. It also doesn’t rely on obvious substitutions like ‘0’ for ‘O’ or ‘4’ for ‘A’. Put yourself in the shoes of a hacker: do you really think they don’t know these tricks already?

A longer password is bad news for hackers because they like to ‘brute-force’ password combinations until they hit a match. If they have to work through more combinations then it’s much harder for them to brute-force your password - a random password of length 25 that draws from a character set of 36 (as in option 2) has 36 to the power of 25 possible combinations. That’s an inconceivable number of combinations and almost impossible to crack by pure brute-force methods.

Given the increasingly prevalent risk of hacking, then, people are more… careful nowadays, right?

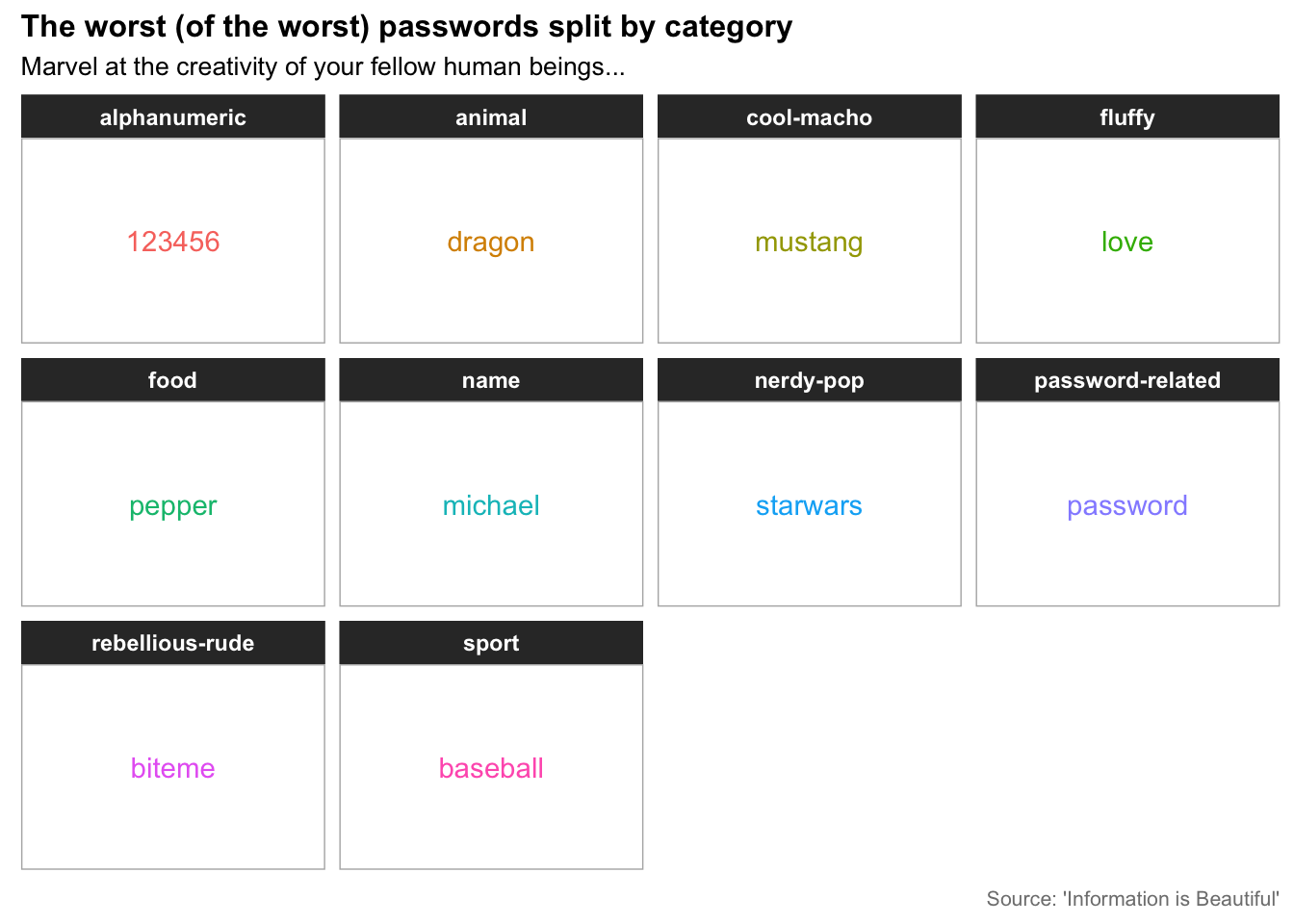

Turns out this isn’t quite true. I performed an analysis of so-called ‘bad passwords’ in the past - courtesy of the fantastic ‘Information is Beautiful’ - and it is fair to say that the results were more shocking than I had originally anticipated,

Yes, some people do lazily resort to the literal string ‘password’ and it is not as uncommon as you might think. If this is you, by the way, then please - for the sake of your online security - change your password right now! Dr Mike Pound has gone a step further than me and suggested that people who do this should delete their account purely out of shame. I’m not so harsh, but you’ve been warned.

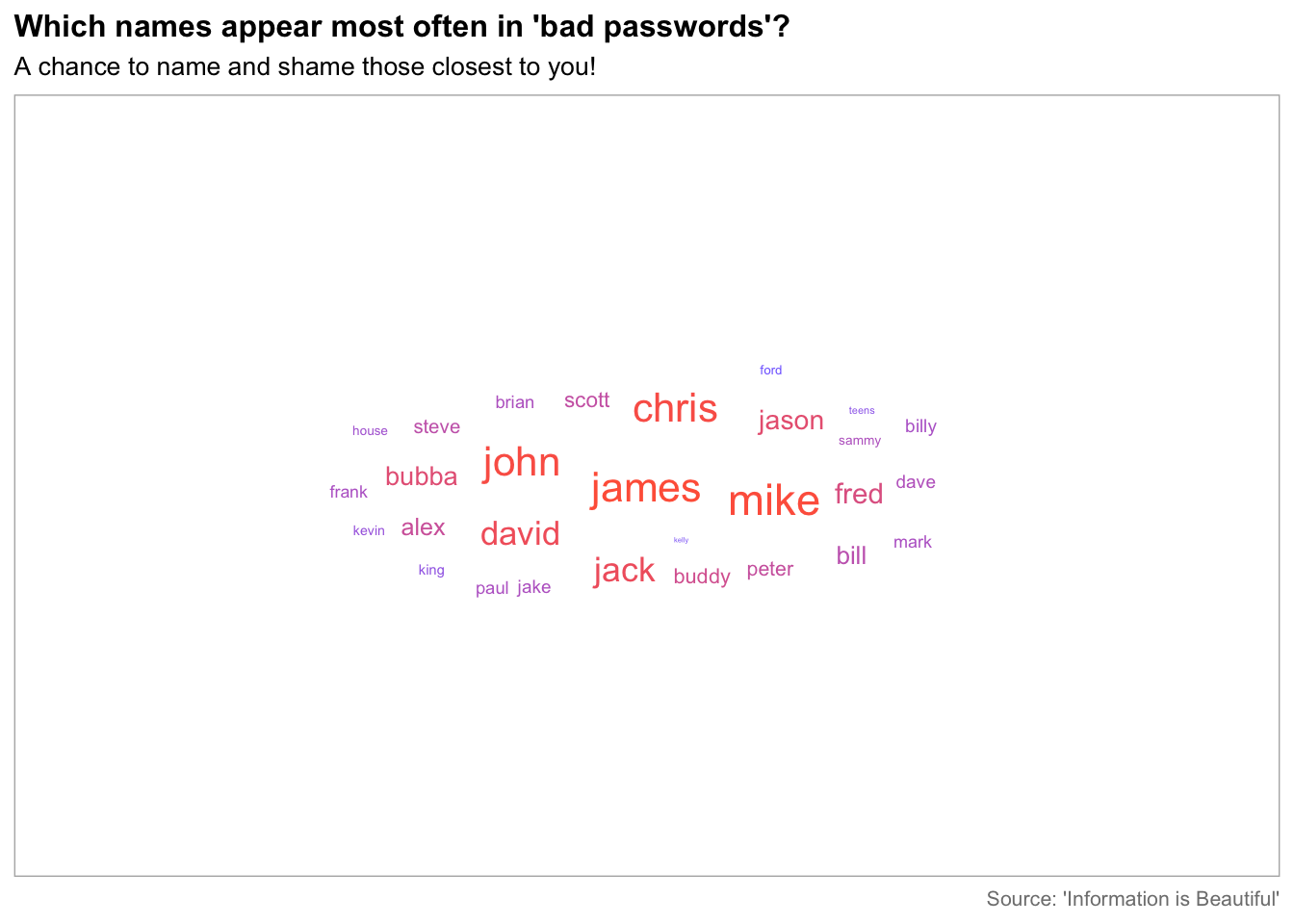

If there were anything worse than ‘password’, it would have to be the use of one’s own name. I like to name and shame those who deserve it so here’s a list of some of the worst culprits,

It’s difficult to get across to people just how poor passwords like these are. A name like ‘mike’ is 4 characters long. If a hacker managed to access a database with Mike’s profile in it, they’d only have to go through roughly 1.7 million combinations in order to crack it. To put this into perspective, Triaxiom Security built a cracking machine worth just $5,000 which could attempt 3 billion password guesses per second.

Of course, most applications nowadays demand users to change things up a bit - you often can’t choose a password of 8 characters or less and you often have to include at least one special character. Even with 8 characters, however, the Triaxiom Security build would still be able to crack your password within the scope of 3 days. That’s quite astonishing when you think about it.

Hackers are not limited to brute-force methods

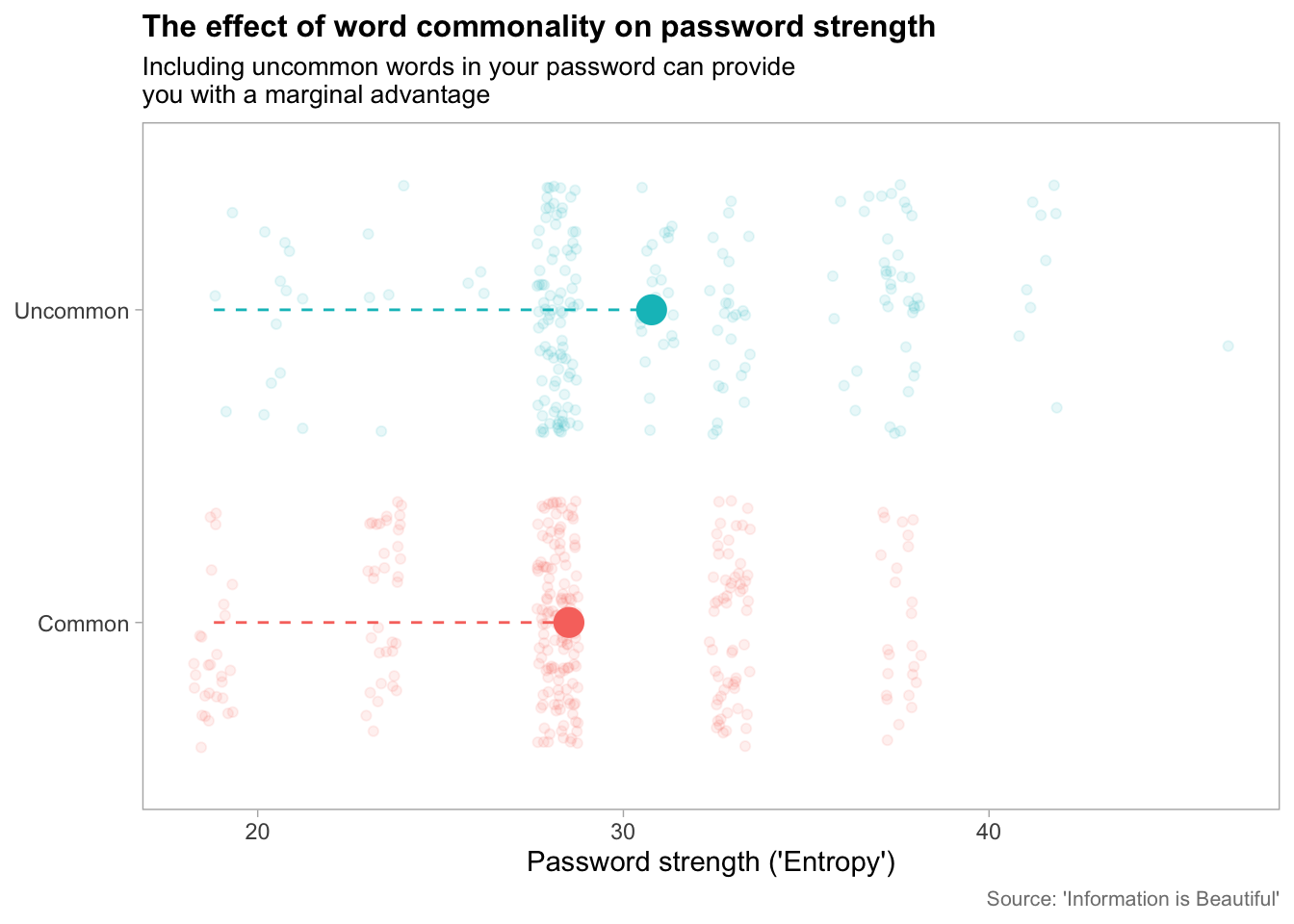

Whilst protecting your password against brute force attacks is all well and good, something you also have to keep in mind is whether your password is ‘dictionary-crackable’. This is where option 2 of our initial example falls down slightly - ‘correct’, ‘horse’, ‘battery’ and ‘staple’ are probably in the top 10,000 most used English words. Including common words in your password negates the strength of your password slightly, even in the case of so-called ‘bad passwords’:

A good strategy, as recommended by Dr Mike Pound in his excellent video on password cracking, is to randomly include a special character within the middle of one of the words. For example, ‘correctho?rsebatterystaple’ effectively acts as protection against dictionary-based cracking and has the beneficial effect of transforming your password into something that can only realistically be solved by methods of brute force - methods which are not ideal on such a long password.

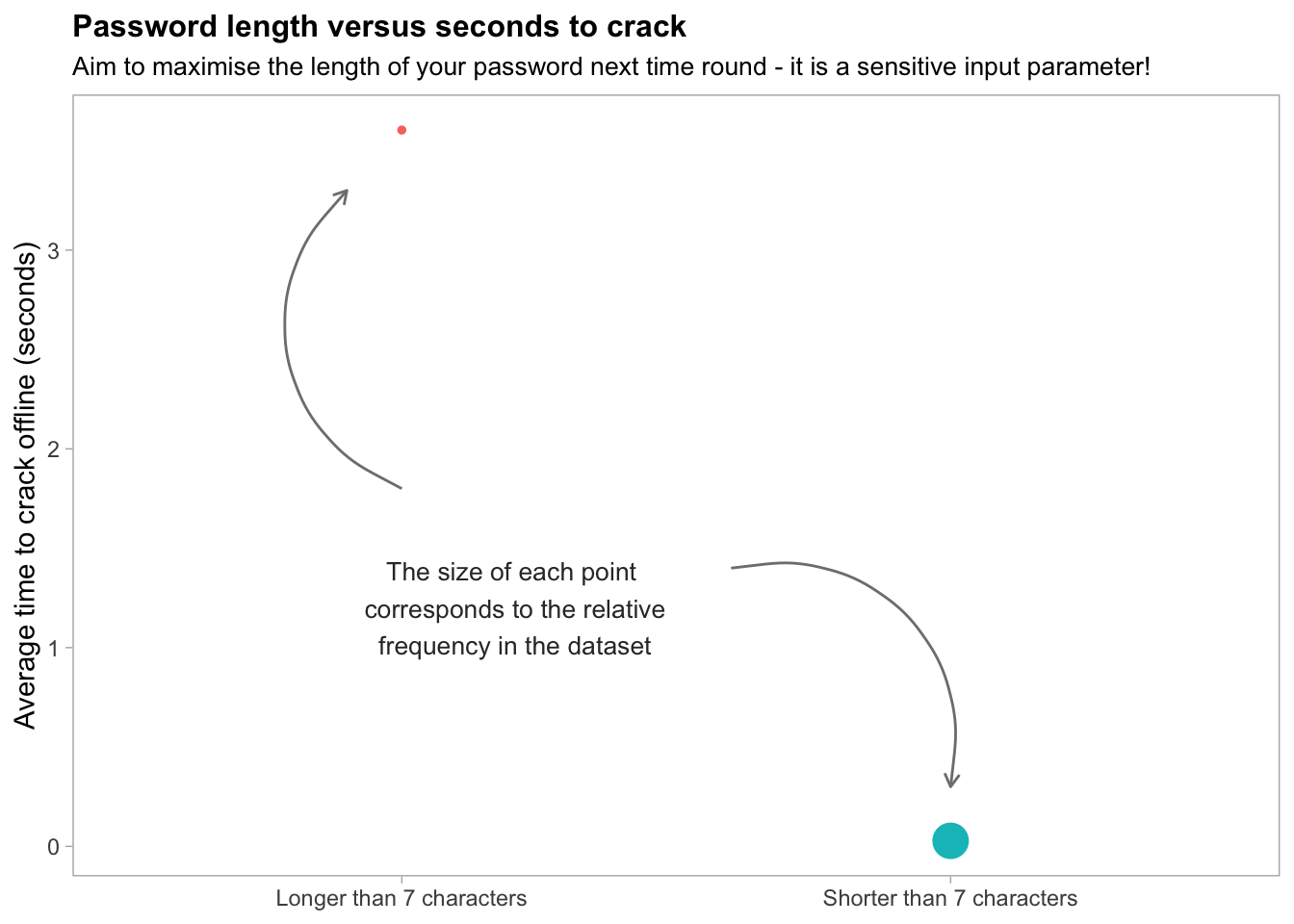

If you are finding all of these rules overly prescriptive and hard to follow just remember: the length of your password is the most important factor. The majority of the so-called ‘bad passwords’ sourced in the aforementioned dataset tended to be 7 characters or less. Such passwords are much easier to crack using an offline brute-force method as can be observed in the graphical summary of password lengths below:

The cardinal rules of password creation

So, what actually makes a good password? Here are some rules you can follow next time you have to make that choice:

- Use a password manager. I highly advise you to look into this at your next available moment

- Prioritise the length of your password above all else and never opt for any password that is less than 8 characters long. Longer passwords are much, much harder to crack!

- Include special characters between component words to avoid dictionary cracking

- Capitalise random parts of each component word in your password

- Avoid common dictionary-based words

If you follow these rules then you can be fairly confident that you probably won’t get hacked!

Footnotes

There has been some debate over this in recent years, particularly because other researchers have struggled to fully reproduce Kahneman’s original conclusions. That said, I think the general idea of humans being ‘lazy’ thinkers is definitely true from experience!↩︎